Abstract

Objective

To examine relations between movement disorders (MD) and psychopathological symptoms in an adolescent population with schizophrenia under treatment with predominantly atypical antipsychotics.

Method

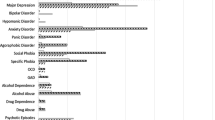

MD symptoms and psychopathology were cross-sectionally assessed in 93 patients (aged 19.6 ± 2.2 years) using Tardive Dyskinesia Rating Scale (TDRS), Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS), Extrapyramidal Symptom Scale (EPS), Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Schedule for Assessment of Negative/Positive Symptoms (SANS/SAPS).

Results

All patients with MD symptoms (n = 37; 39.8 %) showed pronounced global psychpathological signs (SANS/SAPS, BPRS: p = 0.026, p = 0.033, p = 0.001) with predominant anergia symptoms (p = 0.005) and inclinations toward higher anxiety- and depression-related symptoms (p = 0.051) as well as increased thought disturbance (p = 0.066). Both negative symptoms and anergia showed trends for positive correlations with tardive dyskinesia (p = 0.068; p = 0.065) as well as significant correlations with parkinsonism symptoms (p = 0.036; p = 0.023). Akathisia symptoms correlated significantly with hostile and suspicious symptoms (p = 0.013). A superfactor-analysis revealed four factors supporting the aforementioned results.

Conclusion

MD symptoms and psychopathology are in some respects related to each other. Motor symptoms representing on the one hand trait characteristics of schizophrenia might additionally be triggered by antipsychotics and finally co-occur with more residual symptoms within a long-term treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Movement disorders (MD) such as tardive dyskinesia (TD) and extrapyramidal-symptoms as parkinsonism and akathisia are common adverse effects of long-term treatment with antipsychotics (AP). Especially typical AP are known to cause severe MD [54, 77, 80, 86], whereas atypical AP are increasingly being used in juvenile patients [35, 39, 66, 84], due to numerous advantages concerning the incidence of MD, negative schizophrenic symptoms as well as heightened quality of life [7, 24, 64]. We had initially reported on the prevalence of MD in adolescent patients with onset of schizophrenia in childhood or adolescence. Patients treated with atypical AP displayed significantly fewer symptoms of parkinsonism and - as a trend - of akathisia compared to patients with typical AP [41].

While relations between MD occurrences as symptoms of schizophrenia itself and psychopathological symptoms have been discussed–e.g. in the case of catatonic schizophrenia [15, 71] or regarding motor compulsions in prodromal and residual schizophrenic phases [83], relations between AP-induced MD and schizophrenic psychopathological symptoms have rarely been analyzed in detail. In general, there are numerous studies which assessed MD as well as psychopathological symptoms but did not focus on relations between both. These studies are predominantly restricted to adults [e.g. 16, 28, 33] including residual and/or chronic schizophrenic patients [e.g. 12, 30]. In contrast, some studies focused more strongly on relations between MD and psychopathology, but were as well limited to adults [1, 11–13, 17, 18, 20, 21, 27, 29, 31, 34, 38, 48–52, 55, 56, 58, 62, 67, 70, 72, 75, 87, 88, 94–98]. The mean age (estimated from the raw data presented in the studies) is of about 40 years and mostly long-term treated patients were included in these studies. Interestingly, in their study of 45 adult patients with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses (with an neuroleptic-untreated subgroup of 23 patients at admission), Peralta and Cuesta [75] found that negative, parkinsonian and catatonic symptoms are highly related features, while depressive symptoms seem to be a relatively independent dimension of psychopathology in schizophrenia. The authors hypothesized, that there may be a specific behavioural syndrome under AP treatment which may, at times, be clinically indistinguishable from negative, parkinsonian and catatonic symptoms.

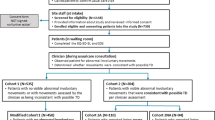

Studies on adolescents as well have mostly described psychopathology and MD symptoms only separately without examining relations between both in detail [e.g. 44, 61, 77, 79, 80, 101]. However, there is, to our knowledge, only one study in 34 adolescents reporting on the relationship between AP-induced MD and schizophrenic psychopathological symptoms [57]. The aim of the current study was to investigate relations of MD with psychopathological findings in a large sample (n = 93) of adolescents who receive predominantly atypical AP for the treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Characteristics of MD and the use of AP in this sample have been described elsewhere [41].

Methods

Subjects

In brief, 93 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder [per DSM-IV] with onset in childhood or adolescence recruited from a rehabilitation center participated in this cross-sectional/retrospective study (see Table 1). Patients were treated on average for 3.6 ± 1.9 years with antipsychotics throughout the course of illness. Three patients (3.2%) were never treated with atypical antipsychotics. At the time of examination 76 patients (81.7%) were being treated with atypical antipsychotics (clozapine 66.7%, olanzapine 10.8%, risperidone 2.2%, sulpiride 2.2%), 10 patients (10.8%) with typical antipsychotics (perazine 3.2%, haloperidol 2.2%, zuclopenthixol 2.2%, flupentixol 1.1%, fluphenazine 1.1%, pimozide 1.1%) and 7 patients (7.5%) with a combination of typical and atypical antipsychotics (clozapine 3.2%, risperidone 3.2%, olanzapine 1.1%; haloperidol 3.2%, levomepromazine 2.2%, perazine 1.1%, thioridazine 1.1%). The mean treatment duration with this medication at time of examination (current antipsychotic treatment) was 2.1 ± 1.4 years meaning that patients were at stable drug regiment. 4 patients (4.3%) were additionally under treatment with SSRIs, 3 patients (3.2%) with tricyclic antidepressants, 4 patients (4.3%) with mood stabilizers. Mean intelligence assessed retrospectively from clinical records was 92.2 ± 13.7 (no statistical gender difference; t-test). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Marburg. Further characteristics of this sample are described elsewhere [41].

Assessment

Psychopathological symptoms were assessed using the Schedule for Assessment of Negative/Positive Symptoms (SANS-K/SAPS-K; 3–6, 85) and the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; 73) including the 5 subscales “anxiety/depression”, “anergia”, “thought disturbance”, “activation”, “hostility/suspiciousness”. MD symptoms were assessed using the Tardive Dyskinesia Rating Scale (TDRS; 90), the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS; 47), the Extrapyramidal Symptom Scale (EPS), a German version of the Simpson Angus Scale [89] and the Barnes Akathisia Scale (BAS; 8, 9). All used instruments are sufficiently reliable and valid [2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 22, 23, 45, 46, 53, 68, 74, 90]. Further details on assessment features and patient groups are given elsewhere [41].

Statistics

To investigate relations of MD with psychopathological findings categorial (group comparison), dimensional (Pearson correlations) and multivariate (superfactor-analysis) statistical approaches were used. Group differences in psychopathology between patients with motor symptoms (n = 37; M-group) and without motor symptoms (n = 56) were studied using two-tailed t-tests or chi-square tests. For the total sample (n = 93) correlations between sumscores of the scales and subscales were evaluated with the Pearson correlation coefficients. Results were calculated as explorative measured values. Furthermore, a superfactor-analysis (with varimax-rotation; n = 93) was performed for the scales’ sumscores. All p values were two-tailed; the significance level was set at .05. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package of the Social Sciences (SPSS 10.0 for Windows) software.

Results

At the time of examination the group of all patient with motor-symptoms with either TD-, parkinsonism- or akathisia-symptomatology criteria (n = 37; see 41) showed significantly higher scores in the SANS- und SAPS-scales (Student’s t-test; p = 0.026 and p = 0.033 respectively), the BPRS-scale (p = 0.001) and the anergia-subscale of the BPRS (p = 0.005) as well as heightened sumscores regarding the BPRS-subscales anxiety/depression and thought disturbance (p = 0.051 and p = 0.066, respectively), if compared to patients without motor-symptoms (see Table 2).

Patients of the group with MD symptoms (n = 37) displayed a significantly younger age at onset of schizophrenia (p = 0.019) and at onset of antipsychotic treatment (p = 0.012) compared to patients without MD symptoms (n = 56) (see Table 1). However, they did not significantly differ with respect to duration or type (typical/atypical) of antipsychotic treatment.

Table 3 shows trends as well as significant correlations between the MD-scales (TDRS, AIMS, EPS, BAS) and the psychopathology scales (SANS, SAPS, BPRS, subscales of BPRS) of the total study sample.

A superfactor-analysis of the sumscores of all MD- and psychopathology scales of the total study sample revealed four factors, explaining 70.2% of variance within the scales: 1. “negative symptoms/parkinsonism/global psychopathology”, 2. “productive symptoms/thought disturbances”, 3. “tardive dyskinesia”, 4. “akathisia/activation” (Table 4).

Discussion

Although MD symptoms are a common phenomenon for patients with schizophrenia under long-term AP treatment, associations between MD symptoms and psychopathological symptoms have been little examined solitarily in adolescent schizophrenic patients treated predominantly with atypical AP. Compared to patients without motor-symptoms all patients with MD symptoms (n = 37) showed higher scores within the psychopathology scales (p = 0.001–0.033), indicative for their aggravated illness; they showed mainly more anergia-symptoms (p = 0.005) as well as tendencies towards more anxiety/depression- (p = 0.051) and thought disturbance symptoms (p = 0.066). This could be explained by patients with worse global psychopathology being treated more often with AP and therefore showing more MD symptoms. Though patient groups did not significantly differ with respect to duration or type (typical/atypical) of antipsychotic treatment, patients with MD symptoms were significantly younger at onset of schizophrenia (p = 0.019) and antipsychotic treatment (p = 0.012), what might suggest, that these patients are predisposed to an increased disease severity with earlier onset of schizophrenia, possibly due to a higher genetic loading.

A superfactor-analysis performed on the scores of the MD- and psychopathology-scales revealed four factors (“negative symptoms/parkinsonism/global psychopathology”, “productive symptoms/thought disturbances”, “tardive dyskinesia”, “akathisia/activation”), which may indicate the existence of different syndrome-like entities as already suggested by Peralta & Cuesta [75].

Relations between movement disorders

Tardive dyskinesia. Dyskinetic symptoms correlate with global psychopathology (p = 0.040), what goes in line with studies in adult patients [49, 67]. Further, in our study dyskinetic symptoms showed a trend towards correlation with negative symptoms (p = 0.068) and symptoms of anergia (p = 0.065), what has also been shown in most of the adult study samples [17, 18, 38, 49, 58, 72, 87, 95–98, overview: 94], whereas other authors could not reveal any linkages [11, 52]. Studies on relations between positive symptoms and TD are comparably rarer [57]. In their study of a small sample (n = 34) of adolescent patients, Kumra et al. [57] found more pronounced positive symptoms in patients with dyskinetic symptoms. Based on the small sample size, these results might be less representative than those found in the current study sample (n = 93). Yuen et al. [100] suggest that the presence of TD may be associated with positive symptoms, while the severity of TD may be related to negative symptoms. According to Waddington et al. [98], the association between negative symptoms and late onset dyskinesia increases with age. A study conducted in untreated adult patients with schizophrenia found no correlations between dyskinesia and psychopathology [62]. Evidence from multiple lines of study indicates that mood disorders, particularly depression, are a risk factor for developing comparably severe TD under AP treatment [26].

Parkinsonism. In the current study, parkinsonism symptoms show correlations with negative symptoms (p = 0.036) and anergia (p = 0.023), a finding which accords with other studies [13, 21, 31, 34, 27, 51, 75]. We found no associations with depressive or aggressive symptoms. Results of former studies about associations of parkinsonism with depressive symptoms are ambiguous [1, 34, 55, 56, 75]. Cheung et al. [29] found more severe parkinsonism side effects in highly aggressive patients when compared to patients with low aggressive behaviour. On the other side it is well known that primary idiopathic Parkinson’s disease goes hand in hand with emotional instability and slowed psychic functions, similar to motor functions.

Akathisia. Akathisia symptoms are correlated with the global psychopathology (p = 0.080) and symptoms of hostility (p = 0.013). As well, two studies reported significant correlations between aggressive behaviour and akathiform symptoms [29, 50]. Some studies revealed connections of akathisia with negative [17, 87] or with depressive symptoms [12, 20], whereas a study of Halstead et al. [48] failed to describe these connections. We could also not identify such relationships, possibly due to the low prevalence of fully pronounced akathisia in our study group (one patient with akathisia and additional 10 patients with subthreshold akathisia symptoms). Nair et al. [70] showed akathisia to predict an increased psychopathology, especially regarding symptoms such as “activation” and “thought disturbance”, what is partly reflected by factor 4 of the superfactor-analysis of our study.

Pathogenic considerations about relationships of MD and psychopathology

Neurochemical hypotheses for TD, parkinsonism and akathisia include changes in dopaminergic, cholinergic, GABAergic and noradrenergic systems, as well as a genetic vulnerability [59, 66, 81, 102]. The anatomical correlative of the linkage between psychopathological and MD phenomena can be seen in the basal ganglia. Especially the striatum is assumed to regulate both motility and mental functions [25]. A dysfunction of the dopaminergic and glutamate system, for example, is likely to result in positive schizophrenic symptoms [25, 53, 76], whereas an imbalance of serotonin and noradrenalin appears to be linked to negative symptoms [14, 60]. Psychomotor activity is determined by interactions of glutamate, dopamine, noradrenaline, serotonin, and acetylcholine [25]. Pharmacological blockage of the D2-receptor may have AP effects within the limbic system [42], although it may be the reason for MD, due to an imbalance of dopamine and acetylcholine [35, 59].

Relationships between psychopathology and MD might be explained by different reasons. First, it is generally assumed that psychopathology results from the pathophysiology of schizophrenia whereas motor symptoms represent side effects of AP treatment. According to this assumption, bias effects based on the cooccurence of more residual symptoms with long-term AP treatment could play a role in relationships between psychopathology and MD. One could hypothesize that patients, which are treated–due to their highly pronounced psychopathology–with high doses of AP, show an enhancement of MD symptoms compared to patients with a reduced global psychopathology. In addition, not only motor but also psychopathological symptoms may be influenced by AP by affecting the basal ganglia [35]. One of the main results of the current study indicating that an increased MD symptomatology is associated with pronounced global psychpathological signs may contribute to this hypothesis.

Second, a common basic pathophysiological principle of both entities could also be postulated, while motor symptoms might not only reflect an integral part of the schizophrenia disease process [31, 62, 83] but also of a specific (genetic) dispostion for the development of drug-induced MD [59, 102] and might thus be triggered by AP [49]. Taking into consideration, that triggering a (genetic) disposition for MD by antipsychotics may be related to the extent of a long-term antipsychotic treatment, this point does not necessarily exclude a common pathophysiology of both entities, which may be manifested in the significant connection of both, MD and global psychopathological symptomatology pronouncement in the current study. In former studies there are as well hints, that antipsychotic medication has not obligingly be present to induce MD symptoms. Reduced premorbid functioning and withdrawal correlate with more negative symptoms and increased extrapyramidal symptoms, even in untreated patients [51, 91]. Imbalances in transmitter pathways could result in motor dysfunctions as well as psychopathological symptoms [25, 32, 36, 40, 58, 65, 75, 81, 99]. As well, neurodegenerative processes may be involved in the pathogenesis of TD, e.g. decreased plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in schizophrenic patients with TD have been found [92]. However, though TD do obviously occur spontaneously in untreated patients with schizophrenia [27, 37, 38, 43, 51, 62, 93], in two studies no correlations with psychopathology were found in these patients [27, 62]. Honer et al. [51] found a tendency for correlation of the severity of MD and negative symptoms in untreated patients.

Third, one could speculate that psychopathological symptoms could in some respect represent secondary reactions to MD symptoms. It has been shown that MD may lead to especially depressive symptoms resulting in a reduced subjective quality of life [12, 34, 82]. According to a recent study under conventional AP treatment subjective well-being depends strongly on motor side effects, whereas in atypically treated and drug-naive schizophrenic patients, subjective well-being is mainly influenced by psychopathological status [78]. Patients of our study sample were mostly treated with atypical AP (92.5%) and MD symptoms in our study sample were generally less pronounced [41], the induction of e.g. depressive symptoms seems rather unlikely. Vice versa, it is known that psychopathology can also lead to MD phenomenons, e.g. anxiety resulting in motor activation.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study have been discussed in detail elsewhere [41]. In brief, due to the cross-sectional/retrospective design causal relationships cannot be inferred and statistical data represent explorative data; we therefore refrained from correcting for multiple testing and as well from covariate analysis due to insufficient retrospective data (e.g. considering dosage data). The listed p-values are therefore merely of an explorative nature. As well, correlations coefficients are comparably low, possibly due to the low prevalence and severity of MD symptoms in this study sample under treatment with predomaninantly (92.5%) atypical antipsychotics, so that sumscores of MD sumscores are mostly very low (see 41). However, the naturalistic character of the study represents the typical clinical features of relations between MD symptoms and psychopathology in this patient population. Second, the generalizability of this study may be limited by the fact that adolescents undergoing rehabilitative treatment were included, which makes it even more likely for MD of a long-term AP treatment and residual symptoms to occur together. Third, some motor and psychopathological symptoms may show partially overlays (e.g. akathisia and activation), whereas other symptoms are clearly differentiated from each other (e.g. tremor and social withdrawal). Thus, for the reason of clear differentiation psychomotor testing with specific reliable and valid instruments has been done (see 10). However, it can not be excluded that there might be syndrome-like entities as revealed by our explorative correlation tests and our superfactor-analysis and as has previously been described by Peralta and Cuesta [75]. Fourth, concerning depressive symptoms only a subscale of BPRS was used, while we suggest a specific depression instrument for future studies.

Conclusions

The current study conducted under naturalistic conditions in the, to our knowledge for the given topic, so far largest sample with adolescent patients undergoing a long-term treatment with predominantly atypical AP suggests that MD symptoms and psychopathology are in some respects connected. These relations could be due to [1] AP treatment, [2] pathophysiology of the disease itself or [3] bias effects based on the cooccurence of residual symptoms and long-term AP treatment. Clinical examinations in AP-naïve and AP treated patients suggest that both psychopathological and motor symptoms occur in schizophrenia, while the latter are additionally enforced by AP treatment. Thus, a (anatomical/pathophysiological) correlative of the linkage between psychopathological and MD symptoms playing a crucial role in both pathophysiology disease and AP treatment, seems to be likely. Due to the exploratory nature of the study causal relationships cannot be inferred and the study allows therefore for further differentiation (e.g. in prospective studies) between MD and psychopathological symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Laboratory and more biologically driven tests that study endophenotypes of negative symptoms or neuromotor abnormalities are required to disentangle the overlapping phenotypic presentations of movement disorders and psychopathology, aiming at better understanding their genesis and building a foundation for a systematic therapy of the disease as well as the pharmacogenetic side-effects.

References

Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E (1994) Specificity of Calgary Depression Scale for schizophrenics. Schizophr Res 11:239–244

Andreasen NC (1982) Negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39:789–794

Andreasen NC (1984) The scale for the assessment of negative symptoms (SANS). University of Iowa, Iowa City

Andreasen NC (1984) The scale for the assessment of positive symptoms (SAPS). University of Iowa, Iowa City

Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Anrdt S, Alliger R, Swayze VW (1991) Positive and negative symptoms: assessment and validity. In: Marneros A, Andreasen NC, Tsuang MT (eds) Negative versus positive schizophrenia. Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer, pp 28–51

Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Swayze VW, Tyrell G, Arndt S (1990) Positive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. A critical reappraisal. Arch Gen Psychiatry 47:615–621

Angermeyer MC (1999) Beeinflussung der Lebensqualität unter Neuroleptika. In: Fegert JM, Häßler F, Rothärmel S (eds) Atypische Neuroleptika in der Jugendpsychiatrie. Stuttgart, New York, Schattauer, pp 219–229

Barnes TRE (1989) A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 154:672–676

Barnes TRE, Halstead SM (1988) A scale for rating drug-induced akathisia. Schizophr Res 1:249

Barnes TRE, McPhillips MA (1995) How to distinguish between the neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome, depression and disease-related negative syndroms in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 10(Suppl 3):115–121

Bartzokis G, Hill MA, Altshuler L (1989) Tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia patients; correlation with negative symptoms. Psychiatry Res 28:145–151

Baynes D, Mulholland C, Cooper SJ, Montgomery RC, MacFlynn G, Lynch G, Kelly C, King DJ (2000) Depressive symptoms in stable chronic schizophrenia: prevalence and relationship to psychopathology and treatment. Schizophr Res 29:47–56

Berardi D, Giannelli A, Biscione R, Ferrari G (2000) Extrapyramidal symptoms and residual psychopathology with low-dose neuroleptics. Hum Psychopharmacol 15:79–85

Bleich A, Brown SL, Kahn R, VanPraag HM (1988) The role of serotonin in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 14:297–315

Bleuler E (1975) Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie. 13th edn. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York, Springer

Bobes J, Gibert J, Ciudad A, Alvarez E, Canas F, Carrasco JL, Gascon J, Gomez JC, Gutierrez M (2003) Safety and effectiveness of olanzapine versus conventional antipsychotics in the acute treatment of first-episode schizophrenic inpatients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 27:473–481

Brown KW, White T (1991) Pseudoakathisia and negative symptoms in schizophrenic subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 84:107–109

Brown KW, White T (1991) The association among negative symptoms, movement disorders, and frontal lobe psychological deficits in schizophrenic patients. Biol Psychiatry 30:1182–1190

Brown KW, White T (1992) The influence of topography on the cognitive and psychological effects of tardive dyskinesia. Am J Psychiatry 149:1385–1389

Burke RE, Kang UJ, Jankovic J, Miller LG, Fahn S (1989) Tardive Akathisia: an analysis of clinical features and response to open therapeutic trial. Mov Disord 4:157–175

Caligiuri MP, Lohr JB, Bracha HS, Jeste DV (1991) Clinical and instrumental assessment of neuroleptic-induced parkinsonism in patients with tardive dyskinesia. Biol Psychiatry 29:139–148

Campbell M, Grega DM, Green WH, Bennett WG (1983) Neuroleptic-induced dyskinesias in children. Clin Neuropharmacol 6:207–222

Campbell M, Palij M (1985) Measurement of side effects including tardive dyskinesia. Psychopharmacol Bull 21:1063–1075

Campbell M, Young PI, Bateman DN, Smith JM, Thomas SH (1999) The use of atypical antipsychotics in the management of schizophrenia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 47:13–22

Carlsson A, Hansson LO, Waters N, Carlsson ML (1997) Neurotransmitter aberrations in schizophrenia: new perspectives and therapeutic implications. Life Sci 61:75–94

Casey DE (1988) Affective disorders and tardive dyskinesia. Encephale 14:221–226

Chatterjee A, Chakos M, Koreen A, Geisler S, Sheitman B (1995) Prevalence and clinical correlates of extrapyramidal signs and spontaneous dyskinesia in never-medicated schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 152:1724–1729

Chengappa KN, Goldstein JM, Greenwood M, John V, Levine J (2003) A post hoc analysis of the impact on hostility and agitation of quetiapine and haloperidol among patients with schizophrenia. Clin Ther 25:530–541

Cheung P, Schweitzer I, Crowley KC, Yastrubetskaya O, Tuckwell V (1996) Aggressive behaviour and extrapyramidal side effects of neuroleptics in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 11:237–240

Conley RR, Kelly DL, Nelson MW, Richardson CM, Feldman S, Benham R, Steiner P, Yu Y, Khan I, McMullen R, Gale E, Mackowick M, Love RC (2005) Risperidone, quetiapine, and fluphenazine in the treatment of patients with therapy-refractory schizophrenia. Clin Neuropharmacol 28:163–168

Cortese L, Caligiuri MP, Malla AK, Manchanda R, Takhar J, Haricharan R (2005) Relationship of neuromotor disturbances to psychosis symptoms in first-episode neuroleptic-naive schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res 75:65–75

Davis EJ, Borde M, Sharma LN (1992) Tardive dyskinesia and Type II schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 160:253–256

de Jesus Mari J, Lima MS, Costa AN, Alexandrino N, Rodrigues-Filho S, de Oliveira IR, Tollefson GD (2004) The prevalence of tardive dyskinesia after a nine month naturalistic randomized trial comparing olanzapine with conventional treatment for schizophrenia and related disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 254:356–361

Dollfus S, Ribeyre JM, Petit M (2000) Objective and subjective extrapyramidal side effects in schizophrenia: their relationships with negative and depressive symptoms. Psychopathology 33:125–130

Dose M (2000) Recognition and management of acute neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal motor and mental syndromes. Pharmacopsychiatry 33(Suppl):3–13

Duncan GE, Sheitman BB, Lieberman JA (1999) An integrated view of pathophysiological models of schizophrenia. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 29:250–264

Fenn DS, Moussaoui D, Hoffmann WF, Kadri N, Bentounssi B, Tilane A, Khomeis M, Casey DE (1996) Movements in never-medicated schizophrenics: a preliminary study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 123:206–210

Fenton WS, Wyatt RJ, McGlashan TH (1994) Risk factors for spontaneous dyskinesia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51:643–650

Findling RL, Steiner H, Weller EB (2005) Use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents. J Clin Psychiatry 66(Suppl 7):29–40

Galderisi S, Maj M, Mucci A, Cassano GB, Invernizzi G, Rossi A, Vita A, Dell’Osso L, Daneluzzo E, Pini S (2005) Historical, psychopathological, neurological, and neuropsychological aspects of deficit schizophrenia: a multicenter study. Am J Psychiatry 159:983–990

Gebhardt S, Härtling F, Hanke M, Mittendorf M, Theisen FM, Wolf-Ostermann K, Grant P, Martin M, Fleischhaker C, Schulz E, Remschmidt H (2006) Prevalence of movement disorders in adolescent patients with schizophrenia and in relationship to predominantly atypical antipsychotic treatment. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 15:371–382

Gerlach J (1995) Schizophrenie. Dopaminrezeptoren und Neuroleptika. Berlin, Springer

Gervin M, Brown S, Lane A, Clarka M (1998) Spontaneous abnormal involuntary movements in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: baseline rate in a group of patients from an Irish catchment area. Am J Psychiatry 155:1202–1206

Grcevich SJ, Findling RL, Rowane WA, Friedman L, Schulz SC (1996) Risperidone in the treatment of children and adolescents with schizophrenia: a retrospective study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 6:251–257

Gualtieri CT, Breuning SE, Schroeder SR, Quade D (1982) Tardive dyskinesia in mentally retarded children, adolescents and young adults. North Carolina and Michigan studies. Psychopharmacol Bull 18:62–65

Gualtieri CT, Schroeder SR, Hicks RE Quade D (1986) Tardive dyskinesia in young mentally retarded individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry 43:335–340

Guy W (1976) ECDEU Assessment manual for psychopharmacology, revised ed. Washington, DC, US Department of Health, Education and Welfare

Halstead SM, Barnes TRE, Speller JC (1994) Akathisia: prevalence and associated dysphoria in an in-patient population with chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 164:177–183

Held T, Weber T, Krausz H, Ahle G, Hager B, Alfter D, Schulze T, Knapp M, Maier W, Rietschel M (2000) Klinische Charakteristika von Patienten mit tardiven Dyskinesien. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 68:321–331

Herrera JN, Sramek JL, Costa JF, Roy S, Heh CW, Nguyen BN (1988) High potency neuroleptics and violence in schizophrenics. J Nerv Ment Dis 176:558–561

Honer WG, Kopala LC, Rabinowitz J (2005) Extrapyramidal symptoms and signs in first-episode, antipsychotic exposed and non-exposed patients with schizophrenia or related psychotic illness. J Psychopharmacol 19:277–285

Iager AC, Kirch DG, Jeste DV, Wyatt RJ (1986) Defect symptoms and abnormal involuntary movement in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 21:751–755

Kay SR (1991) Positive and negative syndroms in schizophrenia: assessment and research. Clinical and experimental psychiatry monograph No.5, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University Montefiore Medical Centre, Bronx, N.Y., USA. New York, Brunner/Mazel

Keepers GA, Clappison VJ, Casey DE (1983) Initial anticholinergic prophylaxis for neuroleptic-induced extrapyramidal syndromes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 40:1113–1117

Kilzieh N, Wood AE, Erdmann J, Raskind M, Tapp A (2003) Depression in Kraepelinian schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 44:1–6

Koreen AR, Siris SG, Chakos M, Alvir J, Mayerhoff D, Lieberman J (1993) Depression in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 150:1643–1648

Kumra S, Jacobsen LK, Lenane M, Smith A, Lee P, Malanga CJ, Karp BI, Hamburger S, Rapoport JL (1998) Case series: spectrum of neuroleptic-induced movement disorders and extrapyramidal side effects in childhood-onset schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:221–227

Liddle PF, Barnes TRE, Speller J, Kibel D (1993) Negative symptoms as a risk factor for tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry 163:776–780

Lowrimore P, Mulvihill D, Epstein A, McCormack M, Wang YH (2004) CAG nucleotide repeat profiles in persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders with and without tardive dyskinesia: pilot study. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 128:15–18

Maas JW, Conteras SA, Miller AL, Berman N, Bowden CL, Javors MA, Seleshi E, Weintraub SE (1993) Studies of catecholamine metabolism in schizophrenia/psychosis-I. Neuropsychopharmacology 8:97–109

McConville B, Carrero L, Sweitzer D, Potter L, Chaney R, Foster K, Sorter M, Friedman L, Browne K (2003) Long-term safety, tolerability, and clinical efficacy of quetiapine in adolescents: an open-label extension trial J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 13:75–82

McCreadie RG, Srinivasan TN, Padmavati R, Thara R (2005) Extrapyramidal symptoms in unmedicated schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 39:261–266

McCreadie RG, Thara R, Kamath S, Padmavathy R, Latha S, Mathrubootham N, Menon MS (1996) Abnormal movements in never-medicated Indian patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 168:221–226

Meltzer HY, McGurk S (1999) The effects of clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine on cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 25:233–255

Miller R, Chouinard G (1993) Loss of striatal cholinergic neurons as a basis for tardive and L-dopa-induced dyskinesias, neuroleptic-induced supersensitivity psychosis and refractory schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 34:713–718

Miller CH, Fleischhacker WW (2000) Neurologische Neuroleptika-Nebenwirkungen. In: Förstl H (ed.) Klinische Neuro-Psychiatrie. Neurologie psychischer Störungen und Psychiatrie neurologischer Erkrankungen. Stuttgart, New York, Thieme, pp 449–478

Miller del D, McEvoy JP, Davis SM, Caroff SN, Saltz BL, Chakos MH, Swartz MS, Keefe RS, Rosenheck RA, Stroup TS, Lieberman JA (2005) Clinical correlates of tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia: Baseline data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial. Schizophr Res 80:33–43

Moscarelli HJ, Maffei C, Cesana BM, Boato P, Farma T, Grilli A, Lingiardi V, Cazzullo CL (1987) An international perspective on assessment of negative and positive symptoms in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 144:1595–1598

Müller P (1999) Therapie der Schizophrenie: Integrative Behandlung in Klinik, Praxis und Rehabilitation. Stuttgart, New York, Thieme

Nair CJ, Josiassen RC, Abraham G, Stanilla JK, Tracy JL, Simpson GM (1999) Does akathisia influence psychopathology in psychotic patients treated with clozapine? Biol Psychiatry 15:1376–1383

Northoff G (2002) Catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: psychopathology and pathophysiology. J Neural Transm 109:1453–1467

Os J, Fahy T, Jones P, Harvey I, Toone B, Murray R (1997) Tardive dyskinesia: who is at risk? Acta Psychiatr Scand 96:206–216

Overall JE, Gorham DR (1962) The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep 10:799–812

Overall JE, Gorham DR (1976) The brief psychiatric rating scale. In: Guy W (ed) ECDEU assessment manual for pschopharmacology. Revised edision, Rockville. Maryland, pp 157–169

Peralta V, Cuesta MJ (1999) Negative, parkinsonian, depressive and catatonic symptoms in schizophrenia: a conflict of paradigms revisited. Schizophr Res 40:245–253

Pietraszek M (2003) Significance of dysfunctional glutamatergic transmission for the development of psychotic symptoms. Pol J Pharmacol 55:133–154

Pool D, Bloom W, Mielke DH, Roninger JJ Jr., Gallant DM (1976) A controlled evaluation of loxitane in seventy-five adolescent schizophrenic patients. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 19:99–104

Putzhammer A, Perfahl M, Pfeiff L, Hajak G (2005) Correlation of subjective well-being in schizophrenic patients with gait parameters, expert-rated motor disturbances, and psychopathological status. Pharmacopsychiatry 38:132–138

Quintana H, Keshavan M (1995) Case study: risperidone in children and adolescents with schizophrenia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:1292–1296

Realmuto GM, Erickson WD, Yellin AM, Hopwood JH, Greenberg LM (1984) Clinical comparison of thiothixene and thioridazine in schizophrenic adoescents. Am J Psychiatry 141:440–442

Reinbold H (1999) Biochemische Aspekte zur Entwicklung extrapyramidaler Störungen durch Antipsychotika. In: Bräuning P (ed) Motorische Störungen bei schizophrenen Psychosen. Stuttgart, New York, Schattauer, pp 131–142

Reine G, Lancon C, Di Tucci S, Sapin C, Auquier P (2003) Depression and subjective quality of life in chronic phase schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 108:297–303

Remschmidt H (2002) Early-onset schizophrenia as a progressive-deteriorating develomental disorder: evidence from child psychiatry. J Neural Transm 109:101–117

Remschmidt H, Henninghausen K, Clement HW, Heiser P, Schulz E (2000) Atypical neuroleptics in child- and adolescent psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 9(Suppl 1):9–19

Remschmidt H, Martin M, Schulz E, Gutenbrunner C, Fleischhaker C (1991) The concept of positive and negative schizophrenia in child and adolescent psychiatry. In: Maneros A, Andresen NC, Tsuang MT (eds) Negative versus positive schizophrenia. Berlin, Heidelberg, Springer, pp 219–242

Richardson MA, Haugland G, Craig TJ (1991) Neuroleptic use, parkinsonian symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and associated factos in child and adolecent psychiatry patients. Am J Psychiatry 148:1322–1328

Sachdev P, Hume F, Toohey P, Doutney C (1996) Negative symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, tardive akathasia and tardive dyskinesia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 93:451–459

Sandyk R, Kay SR (1990) The relationship of negative schizophrenia to parkinsonism. Int J Dev Neurosci 55:1–59

Simpson GM, Angus JWS (1970) A rating scale for extrapyramidal side-effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 212:11–19

Simpson GM, Lee JH, Zoubok B, Gardos G (1979) A rating scale for tardive dyskinesia. Psychopharmacology 64:171–179

Strous RD, Alvir JM, Robinson D, Gal G, Sheitman B, Chakos M, Lieberman JA (2004) Premorbid functioning in schizophrenia: relation to baseline symptoms, treatment response, and medication side effects. Schizophr Bull 30:265–278

Tan YL, Zhou DF, Zhang XY (2005) Decreased plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in schizophrenic patients with tardive dyskinesia: association with dyskinetic movements. Schizophr Res 74:263–270

Turner T (1989) Rich and mad in Victorian England. Psychol Med 19:29–44

Waddington JL (1995) Psychopathological and cognitive correlates of tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia and other disorders treated with neuroleptic drugs. Adv Neurol 65:211–229

Waddington JL (1989) Schizophrenia, affective psychoses and other disorders treated with neuroleptic drugs: the enigma of tardive dyskinesia, ist neurobiological determinants and the conflict of paradigms. Int Rev Neurobiol 31:297–353

Waddington JL, Youssef HA (1986) Late onset involuntary movements in chronic schizophrenia: relationship of “tardive” dyskinesia to intellectual impairment and negative symptoms. Br J Psychiatry 129:616–620

Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Dolphin C, Kinsella A (1987) Cognitive dysfunction, negative symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia. Their association in relation to topography of involuntary movements and criteria of their abnormality. Arch Gen Psychiatry 44:901–912

Waddington JL, Youssef HA, Molloy AG, O’Boyle KM, Pugh MT (1985) Association of intellectual impairment, negative symptoms, and aging with tardive dyskinesia: clinical and animal studies. J Clin Psychiatry 46:29–33

Yoder KK, Hutchins GD, Morris ED, Brashear A, Wang C, Shekhar A (2004) Dopamine transporter density in schizophrenic subjects with and without tardive dyskinesia. Schizophr Res 71:371–375

Yuen O, Caligiuri MP, Williams R, Dickson RA (1996) Tardive dyskinesia and positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. A study using instrumental measures. Br J Psychiatry 168:702–708

Zalsman G, Carmon E, Martin A, Bensason D, Weizman A, Tyano S (2003) Effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of risperidone in adolescents with schizophrenia: an open-label study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 13:319–327

Zhang ZJ, Zhang XB, Sha WW, Zhang XB, Reynolds GP (2002) Association of a polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin 5-HT2C receptor gene with tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 7:670–671

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Novartis GmbH, Nürnberg, Germany. We are especially grateful to Sabine Finkenstein and Regina Stöhr for their additional assistance. We also wish to thank all patients for participating in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gebhardt, S., Härtling, F., Hanke, M. et al. Relations between movement disorders and psychopathology under predominantly atypical antipsychotic treatment in adolescent patients with schizophrenia. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 17, 44–53 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-007-0633-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-007-0633-0